On The Road

On The Road

by: Bill Oetinger 2/1/2010

The Naming of Things

This is a column I have been thinking about for well over a year…a long time in the pipeline. Its inspiration springs from a book I was reading, off and on, for most of the past year. Meanwhile, as I was reading the book and as the idea was bouncing around in some anteroom of my head, just out of reach, month after month, other easier, more obvious columns have been rolling down my little assembly line, bumping this one to the back of the queue.

It doesn’t help that the topic, if I can ever get a grip on it, is only vaguely related to cycling. Nothing too unusual about that with my so-called cycling columns. I often wander rather far afield while ostensibly sticking to the home page of bikes and biking. Most of the time, with a liberal dash of blarney, I can convince myself, and possibly my readers, that no matter how far off I have wandered, I am still writing about riding. In this case, though, it’s even more of a stretch, as I am not so much writing about riding as I am writing about writing about riding. Got that?

Put another way, I am exploring the matter of the written word: how we use language to describe and articulate the world around us; how we describe the experience of riding through that world, of being in and of that world. I am nibbling away at the notion of how language--the naming of things--binds us to the land we live in (and cycle through). Because I write about cycling on a regular basis, I often find myself wondering how the act of writing about the activity affects the activity: is the act of rolling across the landscape on the bike its own, fully contained experience, or is that experience enhanced and illuminated--or possibly diminished--by being described in writing?

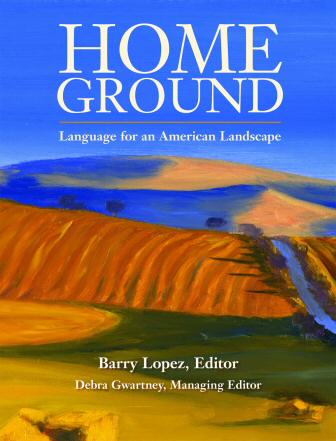

Let's start with that original inspiration: the book. Title: Home Ground; subtitle: Language for an American Landscape. That tells you something about it. It is a glossary, which my dictionary defines as “an alphabetical list of terms or words found in or relating to a specific subject.” That's accurate enough in this case. It is an alphabetical listing and explanation of all the terms and words used to describe the American landscape. Geographical, geological, agricultural, meteorological, botanical terms and words; all the ways we have of defining and codifying our physical world, from words as simple as “mountain” and “valley” to ones as esoteric as “huérfano” and “pingo.”

Let's start with that original inspiration: the book. Title: Home Ground; subtitle: Language for an American Landscape. That tells you something about it. It is a glossary, which my dictionary defines as “an alphabetical list of terms or words found in or relating to a specific subject.” That's accurate enough in this case. It is an alphabetical listing and explanation of all the terms and words used to describe the American landscape. Geographical, geological, agricultural, meteorological, botanical terms and words; all the ways we have of defining and codifying our physical world, from words as simple as “mountain” and “valley” to ones as esoteric as “huérfano” and “pingo.”

The book’s Editor is Barry Lopez. If you know your writers, in particular those who address the subject of environment, you know you will be in good hands with Lopez, winner of the National Book Award for his wonderful Arctic Dreams. But he is only the editor, author of only the introduction. The real authors are many: 46 of them, each of whom has written the definitions for several or many of the terms and words in the glossary. Some are best-selling brand names in the world of letters: Barbara Kingsolver and Jon Krakauer; most are less well known: academics and specialists in their particular, arcane fields of expertise. Almost all of them, in the course of defining and elucidating their topical terms, quote additional authors--from Herman Melville to Cormac McCarthy, from Eudora Welty to E.B. White--to display the words in a literary context.

The result is a substantial volume: over 400 large pages. It’s not the sort of book anyone is going to sit down and read in a few days, cover to cover. Rather, it is a book that takes up residence beside the bed or beside the head, there to be picked up every so often for a snack of a page or two, each page containing another three or four terms or words and their definitions, each definition running to a few hundred words. I at least cannot read more than a few pages at a time of this sort of rich, dense explication, not if I have any hope of understanding or retaining what I’ve read. Which is why the book has been sitting by my bed for all these months, as I slowly browsed my way from “aa” (a type of lava…and a good scrabble word) to “zig zag” (a rock dam).

Defining and examining the words and terms is more than just a scientific itemization of them all. There are subtexts of etymological and anthropological import. America, as we all learn as tots, is a great melting pot of cultures, which of course means a great melting pot of languages. (It is probably no accident that the dominant, official language of this melting-pot nation is English, the most hybridized mongrel language in the history of human society, and like most hybrids, a vibrant, vigorous organism.) Given the many cultural streams flowing into this land, with all of their linguistic variety, it was inevitable that we should end up with a landscape described in a babel of tongues: Spanish llanos and arroyos, French coulees and cirques, English cairns and burrows. And underneath them all, a sort of ethnographic bedrock: the place names of the first settlers, from Mississippi to Mayacama, Mohawk to Miwok.

Are you still with me here? You dropped into my world today with the expectation of reading something about cycling, but thus far, the cycling content has been pretty thin on the ground. So okay, let me throw you a bone; let me see if I can bolt this rambling rumination onto the frame of a bike somewhere, like a couple of overloaded panniers.

Except for a few monkeys and bears in the circus, most cyclists are humans. And what, above all, distinguishes humans from those monkeys and from all the other creatures of this world? Language, or, more precisely, written language. More than our tool-grasping, opposable thumbs, more than walking around on our hind legs, the use of language is what sets us apart. Cyclists, like most humans, have an inclination to observe the world around them and to organize those observations into a handy data base, a reference system driven, for the most part, by words. If you’re reading this column, I am going to assume two things about you: that you enjoy cycling and that you enjoy reading about cycling. I might go out on a limb and make the even more tentative assumption that you like my way of writing about cycling…my point of view. And if that’s the case, then we’re on the same page about reveling in the passing scenery when we’re out there, noodling down the road.

I will concede that not all cyclists share the same inclination to observe the world through which they ride, nor the desire or facility to describe that world in writing (or to read someone else’s scribblings on the topic). I recall a ride where I hooked up with a fellow heading south along Tomales Bay. We were really moving, at least by my standards. We rolled off 60 miles in well under three hours. I took a few good pulls, but he took more. He was in head-down hammer mode, listening to his inner drummer and oblivious to the world around him. I made a comment at one point about the beautiful scenery along the bay--all of it part of some national park or preserve. His response was a single grunt…a sound an above-average pig might make…and as far as I could tell, he never looked up and out at the passing scenery. It simply was of no interest to him.

But I’m convinced he’s the exception and not the rule: that most cyclists will use the front row seat of a bike to take in the world around them, to wonder at it, to reflect upon it, to take it to pieces and put it back together…and, frequently, to use words to do so. Even hardened hammerheads. Once, while chatting with Andy Hampsten, I asked him if, during his races, he ever had time to look around at the passing scenery, the beauty of the French or Italian countryside. I was a afraid he might think this a totally dopey question, the feeble bleating of a silly old tourist. If he did, he was too much of a gentleman to show it. In fact, he responded very enthusiastically: yes! he did indeed notice the passing scenery, and he always promised himself that when his racing days were over, he would come back and take the time to enjoy the wonders of those wonderful landscapes. I suppose the fact that he now runs a cycle-tour operation in Italy is the proof of those words.

So yes, I do believe that most cyclists, to some degree, enjoy observing the world around them, and then enjoy talking and writing and reading about that experience. It helps us to a greater and more refined appreciation of what we have experienced. It allows us to share that experience with others, so that between us, we may all learn from one another, support one another, and thereby come to some greater and more refined understanding of the experience. The bicycle is a wonderful tool, pieced together almost entirely from some of the most fundamental inventions from the dawn of civilization--the wheel, the lever, the pulley--and yet it is man’s greatest invention--the written word--that elevates the experience of the bicycle to a higher plane of sophistication.

When I take my bike for a spin, my highest priority and most profound pleasure is interacting with the wider world: soaking up the sensory overload, the movable feast, be it meadows or ridges, forests or vineyards, orchards or streams. And as I delight in all that color and texture and beauty, it piques my curiosity. I wonder about watersheds. I'm curious about what geology formed those rocks. I puzzle over the types of trees and the variety of birds. If I am to make any sense out of what I see, I had better have at my disposal at least a modest personal glossary of names and explanations: for the landforms; for the flora; for the fauna; for the history of the region.

All of that, collectively, enriches my rides. And naturally, it enriches my writing about my rides, assuming I have the wit to bend those names and details and histories to my task. For better or worse, my real world and my word world are inextricably entwined. I find it hard to appreciate one without the other: the world inspires the words and the words define the world. Having plowed my way through all of those 400-plus pages of the Home Ground glossary, I now feel somewhat better equipped for understanding what I’m looking at out there, and, just maybe, a bit more competent about putting that understanding into words.

However… In spite of my life-long love affair with the written word, I do appreciate the countervailing point of view: that taking the pure, real-world, in-the-moment experience and translating it into a string of little phonetic markers robs the original experience of its fullness and wholeness, as per the old zen bromide, “those who know, don’t say.” I get it that writing about the experience somehow boxes it up into a linear, finite package of mythic shorthand, or, as David Guterson put it: “Now the story you make up starts to take up space otherwise reserved for reality. For phenomena, you substitute epiphenomena. Skew becomes ascendant. The secondary becomes primary.” It was the self-regard of language that got Adam and Eve kicked out Eden. That was the real, the bittersweet fruit of their knowledge. This is nothing new. The world is filled with books filled with words telling us how to get beyond words to that nameless, wordless place where, “once you see it, it is perfectly clear.”

But while I can accept--as an intellectual, spiritual exercise--that such a state of oneness-with-everything is something to be desired, I don’t expect to get there today, nor anytime soon. In fact, it’s a little bit like dieting: I know I would feel better, look better, and function better (go uphill faster) if I lost 15 or 20 pounds…but, dang, I just don’t want to give up all those nice foods I like to cook and consume. It's the same with moving beyond words: I love them too much. Messing about with words brings me so much enjoyment. It is the great, oxymoronic paradox of words that they themselves--our using of them--will perhaps one day move us beyond them…but not today. (As Saint Augustine said: O Lord, help me to be pure…but not yet.”) So until the bright, white light of wordless oneness knocks me off my bike and strikes me dumb, I am going to continue to stir this frothy broth, this saucy stew of language...for better or verse.

Which brings me back to this column: to writing about writing about riding. When it comes to cycling, nothing beats being out there doing it. But when we can’t be out there, the next best thing is talking about cycling…writing about riding. For this old wordsmith, it comes a very close second. I rejoice in being able to weave the word streams together for these BikeCal columns. I thank my fates for having found me this outlet, and I thank all of you, my occasional readers, for being my codependents in this highly addictive activity. Enough of you keep dropping by each month so that the overseers of this site still seem to think it’s worth devoting a little bandwidth to my banter. I’m neither Proust nor Proulx, but I hope my musings here are a little bit better than the production of a million monkeys banging away on a million typewriters, or, for that matter, better than most of the vapid brain farts tweeting up the blogosphere lately.

If you have managed to slog your way through this maundering morass to this, the final paragraph, I salute you!Your perseverance does you credit. You are probably good at riding into headwinds all day too. I didn’t know if I could get to where I wanted to go when I began the piece, and now that I'm wrapping it up, I’m still not sure I got there. You be the judge, and if you think the piece is abstruse now, and only tenuously connected to cycling, you should have seen the other half-dozen paragraphs I deleted. But I had to try. The general premise has been pestering around in my head for such a long time; I needed to dump it all out here, just to clear some space in my attic for other, better ideas.

Bill can be reached at srccride@sonic.net